The Rubin Museum of Art in New York, dedicated to Himalayan cultural objects, has come under scrutiny from local activists who believe that it is using a community exhibition in Nepal to launder its reputation and deflect public accountability from potentially looted objects in its collection.

On July 29, a special exhibition was opened in one of Kathmandu Valley’s monasteries with the museum’s support, in collaboration with the Itumbaha Conservation Society and Lumbini Buddhist University’s museology program. The show consists of three display galleries for which the Rubin Museum provided “advisory and financial support for the documentation, preservation, display and interpretation” of Itumbaha’s collection, according to a text on its website.

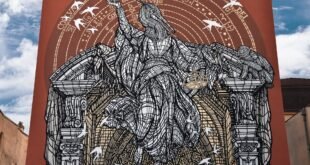

Itumbaha is recognized as one of the oldest and most important Great Mahayana Buddhist Monasteries of Kathmandu Valley. The large two-story Newar Buddhist monastery, owned and operated by a group of monastic elders, is among the largest and most significant examples of 13th-century Nepalese architecture. The vihara (monastery) complex consists of several monasteries, side buildings, courtyards, and shrines, each containing intricately carved columns, windows, doors, and a collection of cultural objects, including sacred statues representing deities. Due to its communal, historical, and architectural importance, its reconstruction has previously been supported by the World Monument Fund. But many of the objects in its collection remained in storage, undocumented and under-researched — until the recent community exhibition.

Like most places of worship in Nepal, Itumbaha has been the victim of looting and trafficking of its sacred items, cultural objects, and architectural elements.

The Rubin Museum of Art was founded by Shelley and Donald Rubin in 2004, who started collecting Himalayan cultural objects in the 1970s — known as the heydays of looting of Nepal’s cultural heritage. The institution’s collection contains dozens of objects from Nepal, most of which are sacred items such as religious manuscripts, Buddhist thangka paintings, and statues of deities. In 2022, the Rubin Museum returned two religious items to Nepal that were confirmed to have been “unlawfully obtained.” One of these was a 14th-century wooden carving of the water spirit Apsara, originally a window decoration at the Itumbaha monastery and purchased by the Rubin Museum in 2003. The online activist group Lost Arts of Nepal first drew attention to the two looted items in 2021 on social media, after which the Nepal Heritage Recovery Campaign requested their return.

These two groups have spearheaded the recent push for the repatriation of looted Nepali cultural heritage held abroad, which in turn has ignited local activism around the protection, ownership, and repatriation of cultural heritage.

Activists are now concerned that the Rubin Museum is using the Itumbaha exhibition to launder its public image and distract from the potentially looted objects the institution still holds. In a recent press release, the Nepal Heritage Recovery Campaign called for a full review of the Rubin Museum collection for potentially looted cultural objects, and warned that the museum’s involvement with the Itumbaha exhibition “cannot be a way to generate misplaced goodwill nor to divert attention from the responsibility of foreign collectors and museums on the matter of stolen heritage items from Kathmandu Valley and Nepal as a whole.”

One day before the exhibition opening, activists demonstrated with signs bearing messages such as “Say No to Cultural Invasion,” “Rubin Stop Your Whitewashing,” and “Rubin We Want Our Gods Back.” Heritage conservationist Rabindra Puri, chairman of the Museum of Stolen Art, told the Nepali Times that “if it is about good faith and goodwill, the museum should investigate its collection and return the Nepali artefacts that are rightfully ours.”

“There could be potential conflict in future repatriation of other sculptures if discovered in the Rubin’s collection,” Puri continued. “There may also be other museums with stolen artefacts that may approach other communities in Nepal to absolve themselves. This is setting a negative precedent.”

In response to Hyperallergic’s request for comment, the Rubin Museum provided a statement by Executive Director Jorrit Britschgi stating that the institution is “sensitive to the issues raised by those who have objected to the Rubin’s support of the Itumbaha Museum” and that they “welcome dialogue with all parties in Nepal in order to center local perspectives.” Britschgi added that the exhibition is “an example of the mutual exchange of knowledge and perspectives that we hope to continue to pursue across the Himalayan region” and that the Rubin Museum is “proactively investigating our full collection and will continue to return any objects that have been stolen.”

The Itumbaha community had wished for a museum to be part of its monastery complex for almost 20 years, to keep the monastery alive and preserve knowledge about its collection.

“We need to understand that this museum has come to fruition exactly because of the repatriation case of two years ago,” said Swosti Rajbhandari Kayastha, curator of the current Itumbaha community museum. “This concept of displaying objects has been part of the vihar for ages. But this new exhibition, driven by the community, is an exciting new era for the Itumbaha collection and for global museology as it foregrounds living heritage.”

“At least the Rubin asked how they could help, and they were very respectful in their collaboration,” Kayastha continued. “Why always look at the negative side? This is a chance to come together and do things correctly. We should acknowledge that this is a positive step in the right direction, and we should commend them for trying.”

Kayastha, who has worked closely with the Itumbaha Conservation Society and other members of the monastic community for the past two years, asserted that the exhibition is “exactly what they want.”

A description of the Itumbaha exhibition on the Rubin Museum’s website that characterizes it as “the first museum in a vihara in Nepal” has also sparked controversy among activists who believe that it turns living heritage into a “lifeless” museum display. Nepal’s sites of worship are open and communal places of worship and knowledge exchange, and some critics argue that the Western notion of a museum is devoid of emotional attachment or traditional learning and is therefore ultimately a form of neocolonialism. Moreover, a museum often emphasizes the artistic or aesthetic features of items on display, rather than their religious or cultural values. This becomes especially problematic when preventing worship of deities in the name of conservation or education.

“Nepal has its own way of exhibiting gods and temple treasures annually during the Bahidyo Bwoyegu ceremony (in which deities of the monastery are displayed),” a spokesperson from Lost Arts of Nepal told Hyperallergic. “We should focus on conserving those traditions instead.”

Source link