The Big Picture

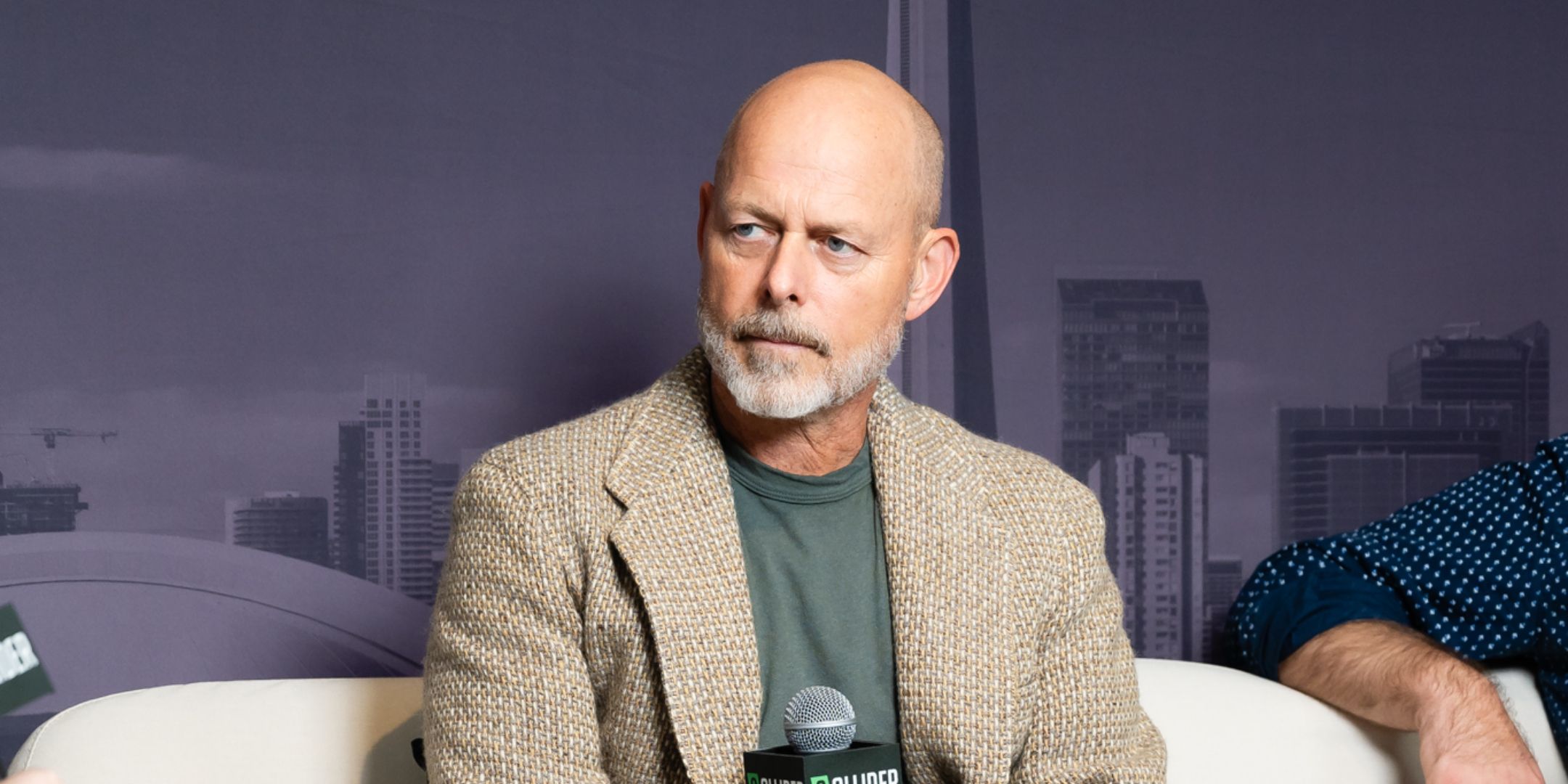

- Collider’s Steve Weintraub talks to director Daniel Minahan and cinematographer Luc Montpellier about

On Swift Horses

at TIFF 2024. - Minahan aimed to portray queer love stories and the fifties realistically, and avoids trying to romanticize or stereotype them.

- Montpellier discusses the time constraints of shooting during magic hour, their approach to intimate scenes and trying to explore the cost of freedom.

Adapted from Shannon Pufahl‘s 2019 novel of the same name, On Swift Horses explores finding queer love and freedom in the 1950s, a time when being queer held far greater risks than now. Newlyweds Muriel (Daisy Edgar-Jones) and Lee (Will Poulter) move to San Diego, where Muriel is waiting tables at a casino. She also meets Lee’s gambling brother, Julius (Jacob Elordi), who just returned from the war, and they discover they have more in common than they thought. Both engage in clandestine relationships that threaten their safety, eventually posing the question — what is the cost of freedom? They are also joined by Diego Calva and Sasha Calle on-screen.

The film premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival 2024, and the director, Daniel Minahan, and cinematographer, Luc Montpellier, talk to Collider’s Steve Weintraub about making a queer film that felt authentic and realistic, rather than romanticized. They also delve into the message they were trying to achieve with On Swift Horses, filming during Magic hour, how they approached intimate scenes and the meaning of the color blue. Hear about it straight from the crew in the video above, or you can read the transcript below.

‘On Swift Horses’ Is The Queer American Dream

“A film about people trying to find love in a time that’s unsympathetic to them.”

COLLIDER: Most people will not have seen the movie yet, so how have you been describing it to people?

DANIEL MINAHAN: I’ve been describing our movie as a romantic film but a reimagining of the American Dream through a queer lens. It starts off as a love triangle and becomes a story about a lot of different kinds of love. I think it’s very surprising and romantic.

100%. One of the many reasons why I enjoyed this movie and one of the reasons why I’m happy it was made is that all too often, especially younger people, you read about it in a book, but you don’t really understand what it was like in different time periods unless you see it. Movies like this open that door to so many people, especially fans of the cast. Can you talk about that aspect?

MINAHAN: Because it’s a film about people trying to find love in a time that’s unsympathetic to them, it has a timeless quality to it. It’s about a lot of different types of love and affection that maybe at that time didn’t have names like we do today, but it addresses all of these ideas. That was important to me. By making it a period film, it gave us the freedom to really explore these things without having to look at them through a contemporary lens.

‘On Swift Horses’ Cinematography Has A Realistic Documentary Feel

The film wanted to avoid “romanticizing the ’50s to the point where it’s inaccessible.”

Obviously, you guys had a meeting to figure out how you’re gonna work together. Talk about those conversations and how you decided on the cameras you wanted to use and the lenses and how you wanted it to look on-screen.

MINAHAN: Which came first? The cameras came second once we decided what we wanted the film to look like. I’ll just kick it off by saying we made a decision early on that we wanted to use documentary photography as a reference. We ended up pulling images of paintings and different things from the period but not looking at period films. Because this film has aspects of melodrama, of film noir, of the romantic film, we wanted to avoid those tropes and really put the emotions of the characters first. The photography afforded us a kind of verisimilitude. Luc can talk about the palette of the piece and the reason you chose these cameras better than I can.

LUC MONTPELLIER: One of the key things Dan told me early, which I think framed everything for me, is this idea of not romanticizing the ’50s to the point where it’s inaccessible. Hence, the documentary reference. I always kept that in my mind that you want people to feel like they were there. That’s what I felt.

MINAHAN: That’s what we kept saying. We didn’t want it to feel nostalgic. We did the same thing with the music. We had a lot of music on set to bring the actors there. We always wanted it to be things that we didn’t recognize.

MONTPELLIER: Everything was drawn from that initial concept. As a cinematographer, you start thinking of your tools. For me, it was blending the most modern cameras, which is a lot of what we have access to, but finding a sensor in the digital world that has a very organic grain. The red cameras I’ve been really obsessed with recently, but then you mix that in with a vintage lens that we were able to actually de-tune. I actually worked with the rental house in LA, in Panavision, and was able to literally design optics that took the edge of the digital nature because also we’re representing the ’50s. A lot of the photography Dan’s talking about, a lot of them aren’t aged. They’re very vibrant and, Dan kept saying, full spectrum of color, which to me is realism. It was a real challenge. You also don’t want the film to feel too digital in a way. So, I used a lot of post-production looks that were based on old film stocks, too. It transferred all the colors which seemed to fit within the direction we were going.

MINAHAN: And then things started happening naturally. As Luc and the production designer and the costume designer got into a groove, there are things that we noticed, especially when we were doing the color timing. I didn’t want to have a designed palette. I wanted the palette to be a full range of the spectrum of color, so that it felt like the real world, rather than something super controlled. What starts to happen as Muriel pursues her truth and follows her instincts towards her right life, everything takes on this blue hue — the costumes are blue, the set of the gay bar she goes to is blue. It’s interesting. Things like that happened just instinctively.

It’s so interesting because the average person is not gonna realize the blue. They’re not gonna catch certain things. It’s gonna be the people that study the movie that will put it together. But it’s so interesting because, subliminally, I think they do pick up on these things.

MINAHAN: I think so, too. And blue, traditionally, is a color of truth. Jeriana [San Juan], our costume designer, chose things very purposefully in colors that were unique to the period, also. That was fun. It was fun watching that happen. When you collaborate with a group of people you really trust, it just starts to flow. It’s not a labored or overly designed thing.

David Minahan Wanted to Avoid Queer Stereotypes

Something I also want to compliment you on is that, all too often in a film like this, you could easily have the husband being an antagonist or being an asshole, but there’s really no antagonist in the conventional narrative movie. Talk about that aspect of the film and why it was important all of them are good people.

MINAHAN: In the more conventional version of this story, the husband would be abusive, the brother would have this lonely life. Of course, the queer people’s lives would all end tragically, either in solitude or being murdered or suicide. The thing that attracted me to this material, Shannon’s [Pufahl] novel, was that it didn’t have that. It reminded me of gay and lesbian people who were friends with my parents in the ’70s when I grew up, who were just living their lives in suburban Connecticut. I don’t know that they had easy lives, but they were a part of our lives. These are people who are just getting on with their lives, and in a way, it’s like the mundane aspect of building a life and a family in a time that is historically unfriendly to you.

The Magic Hour Presented Some Not-So Magic Challenges

Talk about what shot or sequence ended up being the real pain in the ass for the two of you.

MINAHAN: Oh, wow. Did we have a hard one?

MONTPELLIER: Maybe it was Magic Hour in general. The time you probably wanted to strangle me the most, you’ve told me. [Laughs]

MINAHAN: They’re all in the film, but it’s a slightly changed version of it. Shooting at Magic Hour, to be able to use it as night and to just have that incredible luminous quality that the world takes on at that time gave us a very narrow margin of time to shoot entire scenes.

You should explain to people who don’t realize what Magic Hour is and how limited that time is.

MONTPELLIER: It’s that beautiful time between when the sun sets and full night occurs. You still have that glowing beautiful light in the sky. It’s a really important time if you’re trying to create a timeline, but also having our night exteriors be luminous and glowing. Because Julius is searching for Henry the entire time, and time is running out. The light is fading, so it lasts maybe 30 minutes at the most.

I thought it was like 15, but I could be wrong.

MONTPELLIER: With these new cameras, you can extend it, so I’m being generous. But that’s a real challenge on the performers, the actors. We spoke a lot about, “We don’t have a lot of time. How are we going to do it?” If you’re not getting it, you still don’t have an option for a take two sometimes. It was a real challenge, but I think it has a real place in the film and the arc of it.

MINAHAN: It gives it a kind of urgency, too. Then you yell at each other, and then you move on. “We’re never doing that again…until next week.” [Laughs] There’s a beautiful one when Muriel comes back from the bar, where she meets the woman from the racetrack. She’s kind of drunk, and she’s walking down the street holding her shoes, and then she hears a party, and she walks to the neighbor’s house to crash this party. It is so exquisite. It’s really, really worth it.

Intimate Scenes in ‘On Swift Horses’ Changed With Location

There are some intimate scenes between Jacob [Elordi] and Diego [Calva] and Daisy [Edgar-Jones] and Sasha [Calle]. Talk a little bit about how you wanted to photograph and other things. How did you decide you wanted to photograph these scenes and depict certain sequences?

MINAHAN: We set some rules for ourselves which just seemed organic. When we’re in, let’s say Kansas, it had a very formal film language. When we were in the housing development, it had a kind of rigid quality to it because we wanted it to feel confining. When we were in the private spaces with the queer characters, we were always handheld — it was the one place, in these small places, where they could be free. We encouraged improvisation, but we encouraged the operators not to be afraid of making messy frames, not to be afraid of lens flares, so that it had an authenticity to it or a kind of roughness to it. We also really choreographed and rehearsed those with the actors. That was how we got to it.

MONTPELLIER: I just wanted to say exactly what’s beautiful about that is this contrast of that American dream, very formal frame, and you almost have to have some place to go. I appreciated your guidance on, “Let’s not over-plan this. Let magic happen on the day.” I remember you saying that to me, “Let’s just be in the moment.” But having those things contrast each other really gave weight to those intimate moments.

MINAHAN: When we first met, we talked about this. Because the thing that attracted me to Luc’s work was I’d seen Women Talking, which is incredibly controlled and beautiful, but also tells tales from the loop. I feel like he made some of the best hours of series I’ve ever seen. That also had a very specific, very controlled look, and he was fearless and absolutely threw himself and his crew at it and created lighting setups and encouraged the kind of improvisational feel to it. That was fun.

Dialogue Was Stripped From ‘On Swift Horses’ in Post-Production

“The cost of freedom is you’re gonna hurt a lot of people along the way.”

I always like talking about the editing room because it’s where it all comes together. So how did this film change in the editing room in ways you didn’t expect going in?

MINAHAN: It was a novel that was very interior. There wasn’t a lot of dialogue in the novel. With the writer, we had to give these people voices, and, interestingly, in the editing of it, we pulled a lot of dialogue out. I kept saying to Daisy Edgar-Jones, “I think you would have been one of the great silent movie actresses,” because she doesn’t really talk until the last third of the film when she meets Sandra. She really opens up, and you realize at that point, she’s always measuring herself against these men and other people. Then she opens up, and you get to really find out who she is. That was part of the editorial process. Paring it down and seeing how much you could remove and make it still stand. Interestingly, it brought the emotion, the romantic part of it, forward more because these are two characters who are always watching people, and they’re always hiding themselves. We encouraged the editor towards that.

Did you end up with like a lot of deleted scenes?

MINAHAN: There were a number. There was more with the horse. Horses always eat up a lot of time. There was more with the horse that Julius springs, which we found it was just more effective without those scenes. We just removed some of the horse stuff and pared down a lot of the dialogue, so where there were big speeches, they really had weight.

The obstacle of the film is figuring out how to live an honest life, even if it means hurting the people you love.

MINAHAN: That was one of the things that really came forward as we were working on it is the price of freedom. The affection between Muriel and Julius is this kind of love where she’s in love with his freedom, and he’s in love with the idea of belonging somewhere. He’s trying to make a relationship with Henry, and she’s trying to go out into the world and be independent and hiding money and has all of these escape plans. The cost of freedom is you’re gonna hurt a lot of people along the way.

Special thanks to this year’s partners of the Cinema Center x Collider Studio at TIFF 2024 including presenting Sponsor Range Rover Sport as well as supporting sponsors Peoples Group financial services, poppi soda, Don Julio Tequila, Legend Water and our venue host partner Marbl Toronto. And also Roxstar Entertainment, our event producing partner and Photagonist Canada for the photo and video services.

Source link