David Bowie was a strange phenomenon. He emerged onto the mainstream at the tail end of the 1960s with his first major hit, “Space Oddity,” an atmospheric ballad about the doomed mission of an astronaut longing for home. It capitalized on the current fascination with space exploration, established Bowie as a keen musical storyteller, and arguably introduced a theme that his work would carry on for many years. But as much as Bowie’s compositions caught the public imagination, there was something about him as a person that was undeniably compelling. A pale, waifish figure with odd eyes brought about by a schoolyard fistfight, his look and presence was quite alien, and his later incarnation as his Ziggy Stardust character shook up the world of glam rock and leaned into his strikingly otherworldly persona.

‘The Man Who Fell to Earth’ Was David Bowie’s First Feature Film

So, when acclaimed art film director Nicolas Roeg set about adapting Walter Tevis’ classic sci-fi novel The Man Who Fell to Earth, Bowie was just about the perfect person to bring to life the character of Thomas Jerome Newton, an alien who ventures to Earth to build a technology empire that will fund rescue efforts for his own dying home planet. Roeg happened upon the rocker on TV, and according to his memoir, The World is Ever Changing, was struck by his presence.

“I really came to believe that Bowie was a man who had come to Earth from another galaxy. His actual social behavior was extraordinary. He brought with him a trailer full of books and things; he hardly mixed with anyone at all. He seemed to be alone, which is what Newton is in the film – isolated and alone. I can’t imagine now anyone else in the part. David Bowie is Thomas Newton.”

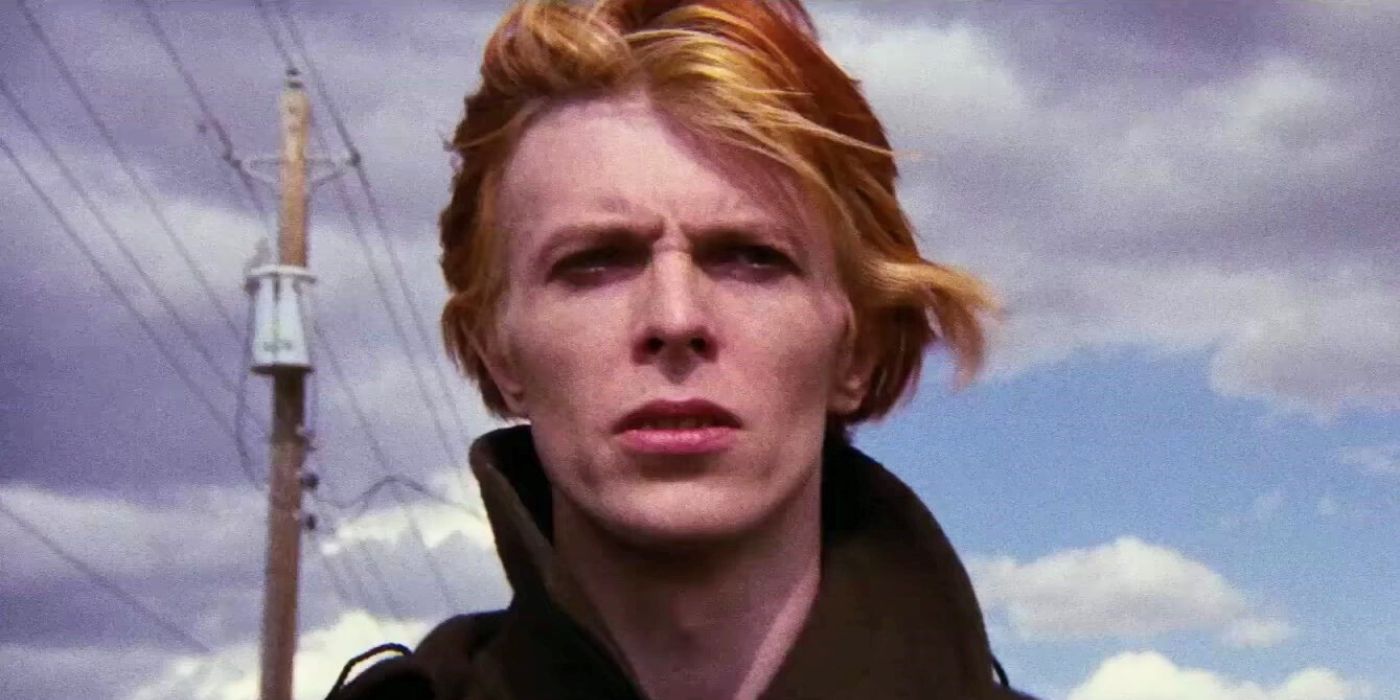

Despite the desirability of a transition from music into film, and having wanted to do so for a while, it was not a move that came easily to Bowie, and he was nervous about his capabilities and how he would be perceived. On top of it, like many rock stars of the era, Bowie was living with a considerable cocaine habit and his own sense of alienation. He was also in the process of shedding his Ziggy character and moving on to a new incarnation, and was desperately trying to find himself. This new foray into cinema could prove to be the next chapter in his artistic career. So he packed up his books and headed for New Mexico for this exciting new venture.

What Is ‘The Man Who Fell to Earth’ About?

The Man Who Fell to Earth is not a movie for the average sci-fi goer. If you’re hoping for space travel and cool alien creatures, you will not find enough of them in this picture for your liking. The movie is a very people-based drama with lashings of that trademark Roeg surrealism, a strange soundtrack, and a bunch of bemusing sex scenes. The almost incomprehensible nature of the movie is not helped by what is really a poor adaptation of Tevis’ novel by screenwriter Paul Mayersberg, which changes character dynamics, eradicates important interactions while filling in the gaps with nonsensical padding, and seems so choppy that one could assume that half the movie ended up on the cutting room floor.

Tevis’ novel in a nutshell goes like this: Newton has come from the planet of Anthea, which is highly technologically advanced but dying due to a series of wars, and he builds an empire with the technologies of his home planet. However, the physical conditions of Earth are very oppressive to him, and the social conditions even more so. A woman named Bettie Jo becomes his confidante/secretary and Dr. Nathan Bryce, intrigued by these impossible technologies Newton introduces, seeks him out and becomes a lead scientist on his project to bring the surviving Antheans to Earth. However, as the years drag by, Newton falls prey to human vices, namely alcohol and dejection, and the FBI seize him, subject him to experiments that leave him blind, and he gives up on his rescue mission, tired of the world and left to wallow in an unseeing drunken stupor for the rest of his days. It is really a story about the corrupting nature of mankind, and how it eats away at pure intentions. Mayersberg’s script veers somewhat off course, and jumps around so sporadically that the build-up and momentum achieved in the novel is lost. Now Bettie Jo is Mary-Lou (Candy Clark) and Newton’s exhausting lover Bryce (Rip Torn) is a chronic student-seducer who finds new life in his work, and Newton himself becomes not only demoralized but actively hostile himself.

‘The Man Who Fell to Earth’ Isn’t the Best Movie, But It Has Its Strengths

It’s true, the story doesn’t hang together, and Roeg’s penchant for the surreal does not help the more casual viewer to decipher his code. But what really brings it all together is a sense of unreality, both in the atmosphere of the film, and in Bowie’s performance. It is a very experimental film that doesn’t care to hold the viewer’s hand and zips around all over the place with little regard for coherence or linearity. Characters love each other in one scene and in the next are arguing violently, or suddenly come to conclusions without any regard for the thought and suspicion that have built up to them.

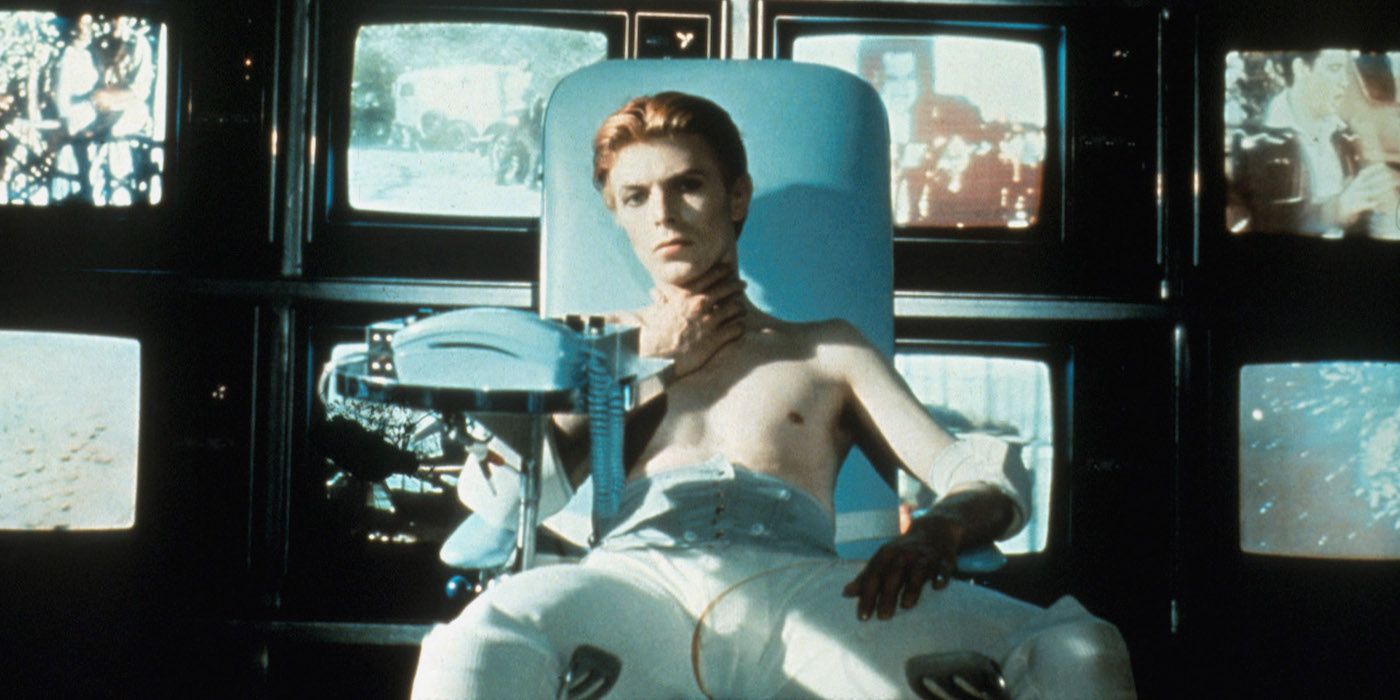

If there is one thing that the movie is memorable for, it is the money shot scene (which incidentally doesn’t happen in the book) where Newton decides to show his true form to Mary Lou. He strips off the eyes, fingernails, and genitals that make up his human costume and emerges from the bathroom bald, amorphous, with yellow cat-like eyes, and Mary Lou collapses into utter hysterics, even wetting herself in fear. It’s such a captivating scene that really captures the uncomprehending panic that an alien on Earth would instill, with brilliantly mysterious cinematography by Anthony B. Richmond and uninhibited realism from Candy Clark as Mary Lou. Moreover, it’s the one scene that actually takes itself completely seriously, and it is to Roeg’s credit that this is where he decides to restrain himself and pull back on the goofy, wink-wink vibe that the rest of the movie gives off.

Why David Bowie Was Such a Perfect Fit for Thomas Jerome Newton

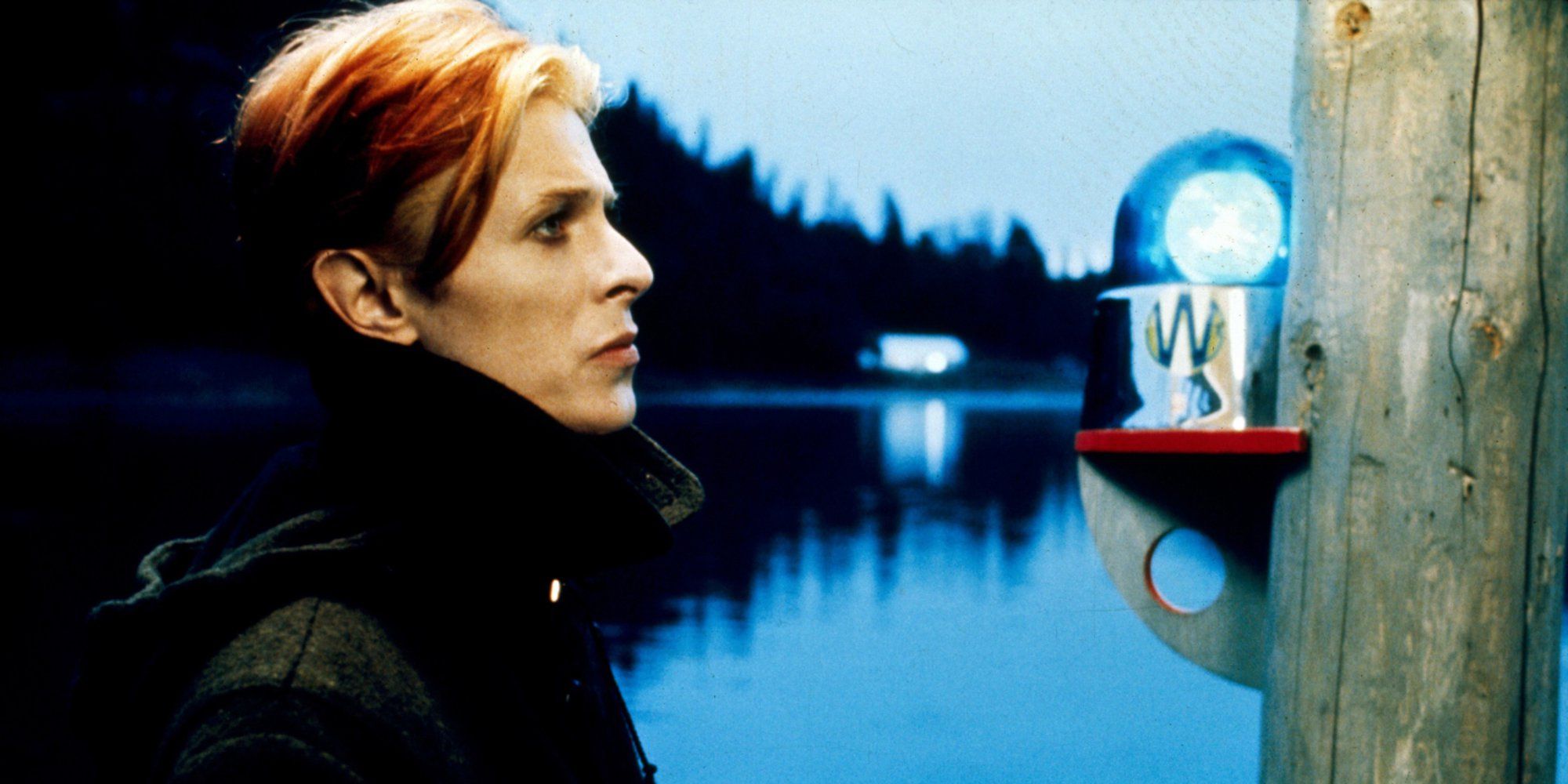

There is a combination of real-life factors that help to build Bowie’s overall aura of strangeness: his own personal struggles and nerves, his inexperience as a screen actor, and his strength as a physical performer under the tutelage of renowned mime artist Lindsay Kemp bring about a being who is never quite sure of himself, and feels subtly out of place. He never really seems to interact with his surroundings — they just happen around him. The first shot of Newton that sees him clad in a thick wool overcoat, stumbling down a cliff side in the desert, is a great piece of physical performance, as he operates his limbs as if they are newly-fitted prosthetics. There is a hint of Scarecrow from The Wizard of Oz about his movement. His early interactions with other people are laden with awkwardness: he fumbles about trying to put on a pair of glasses; he flinches when a lawyer does not take an envelope he offers. As the movie progresses, he seems to become more able to move his body and associate with people in slightly less unnerving ways, but he retains that core element of otherness. His reactions are understated, his conversations disjointed, his interactions disinterested.

It’s a really interesting role for Bowie, as despite his otherworldliness, he was always able to bring energy and vibrancy to his stage performances. His gender-fluid charisma made him one of the many rock stars who embodied the loud, flamboyant, scene-stealing attitude of the 1970s, alongside the likes of Mick Jagger and Iggy Pop. It was an era of standing out in the wackiest and most exciting ways imaginable. So the role of Thomas Jerome Newton allows him to recede within himself and explore the character’s emotions and struggles in a tamer and more understated way. Here he is remarkably cerebral and self-contained, never quite showing the full extent of any singular emotion. There is a sense that he is always thinking, yet never really thinking at all, his head just an empty space. His character goes from nervous, uncomfortable foreigner, to strange but increasingly confident reclusive business magnate, to utter asshole whose mission has evaporated and his kinder and more welcoming tendencies even more so.

David Bowie Establishes Himself as an Actor in ‘The Man Who Fell to Earth’

The Man Who Fell to Earth was a brilliant springboard for Bowie’s foray into acting on both the stage and screen. A few short years later, he played John Merrick in the Broadway production of The Elephant Man to glowing reviews, a role he held dear but found quite exhausting. Again, the role made the most of Bowie’s natural and learned alienness and allowed him to captivate a stage audience in an entirely different way. He would carry on with periodic screen appearances in pictures like The Hunger, Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, and The Prestige, but undoubtedly his most iconic role is that of Jareth the Goblin King in Jim Henson’s 1986 masterpiece Labyrinth. By this point he had obviously found his feet as an actor and brimmed with confidence and charm, no doubt helped along by the heavy use of music in the film.

The Man Who Fell to Earth is most definitely an acquired taste. Even this Bowie fan has given it several goes over the years, only to still not find it an entertaining or coherent movie. But it’s definitely an interesting one that showcases Nicolas Roeg during his golden era, plays with some interesting visuals, and serves up more amusingly surreal sex scenes than any fan of indie ‘70s cinema could ask for. And by God, it is just so perfect for Bowie. Just as Madonna would find in the ‘90s with Alan Parker’s Evita, the role is so well-suited to Bowie that he seems born for it. His presence is captivating, his energy unique, and while determined to prove himself, he demonstrates the creative restraint needed to really make the character what it needs to be. Any Bowie fan or lover of surrealist cinema should check it out at least once and really soak in all the ambiance it has to offer. It’s quite a ride.

Source link